In a dramatic military operation that stunned the world, US forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on January 3, 2026, and flew him to New York to face drug trafficking charges. What made this event particularly significant was President Donald Trump's justification for the action: he called it an update to the Monroe Doctrine, a 200-year-old US foreign policy that has shaped America's relationship with Latin America for two centuries. This bold move raises fundamental questions about how this historical doctrine works, why it remains relevant today, and what it means for the future of US-Latin American relations.

The Monroe Doctrine Explained: America's Original Sphere of Influence Policy

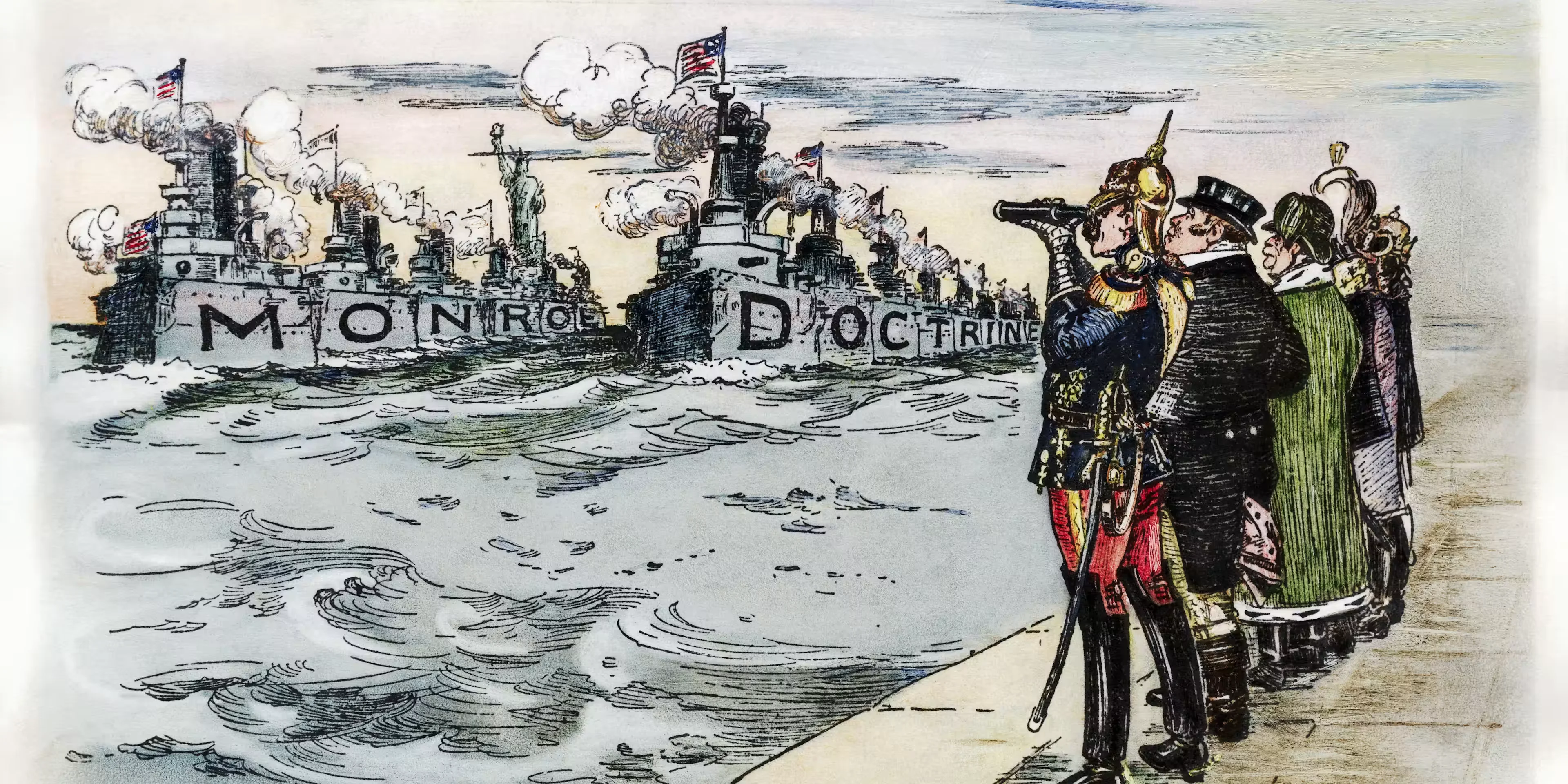

The Monroe Doctrine isn't a law or treaty, but rather a foundational principle of US foreign policy that has evolved over two centuries. First articulated by President James Monroe in his December 2, 1823, address to Congress, the doctrine established what historians call "separate spheres of influence" for the Old World and the New World. At its core, the policy warned European powers not to attempt further colonization or interference in the Western Hemisphere, stating that the United States would view any such interference as a potentially hostile act.

The doctrine emerged at a time when many Latin American countries had recently won independence from Spain and Portugal. Both the United States and Britain worried that European powers might try to reclaim their former colonies. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams convinced Monroe to make a unilateral declaration rather than join forces with Britain, arguing this would set an independent course for the young nation and assert its role as protector of the Western Hemisphere.

Monroe's message contained three key principles that define how the doctrine works: First, the United States would not interfere in the political affairs of Europe. Second, the US would recognize and not interfere with existing European colonies in the Western Hemisphere. Third, and most importantly, "The American continents... are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers." This last principle established what would become America's claim to hemispheric leadership.

From Roosevelt to Reagan: How the Doctrine Evolved Over Two Centuries

Initially, the Monroe Doctrine was more aspiration than reality—the United States lacked the military power to enforce it. European powers largely ignored the declaration, and the US itself declined to act when Britain occupied the Falkland Islands in 1833 or when European navies blockaded Argentina in 1845. However, as American economic and military strength grew, so did its ability to back Monroe's words with action.

The doctrine took on new life in 1904 when President Theodore Roosevelt added what became known as the Roosevelt Corollary. Roosevelt asserted that the United States had the right to intervene in Latin American countries to prevent European interference, particularly concerning debt collection or instability. "Chronic wrongdoing... may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation," Roosevelt declared, adding that in the Western Hemisphere, the US might have to exercise "an international police power."

This "Big Stick" policy justified US military interventions throughout Central America and the Caribbean in the early 20th century, including in the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Cuba. During the Cold War, presidents from John F. Kennedy to Ronald Reagan invoked the doctrine to justify actions ranging from the Cuban Missile Crisis naval quarantine to interventions in El Salvador and Nicaragua. The 1989 US invasion of Panama to capture Manuel Noriega represented another dramatic application of the principle that the United States could remove leaders it deemed threatening to hemispheric stability.

The Venezuela Operation: Monroe Doctrine in the 21st Century

The January 2026 operation that captured Nicolás Maduro represents perhaps the most direct application of Monroe Doctrine principles in modern history. The operation, code-named "Absolute Resolve," involved approximately 150 aircraft taking off from 20 different airbases across the Western Hemisphere. US Special Forces captured Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, from their compound in Caracas and transported them first to a US Navy ship, then to New York to face federal charges including narco-terrorism conspiracy.

President Trump explicitly linked the operation to the historical doctrine, stating at a press conference: "The Monroe Doctrine is a big deal, but we've superseded it by a lot, by a real lot. They now call it the Donroe document." He added, "American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again." Trump announced that the United States would temporarily "run" Venezuela and tap its vast oil reserves, the largest in the world, while overseeing what he called a "safe, proper and judicious transition."

The legal justification for the operation has drawn immediate criticism from international law experts and some US lawmakers. Critics point out that Congress has not specifically authorized military action in Venezuela, and the United Nations Security Council has scheduled an emergency meeting to discuss the operation's legality. However, administration officials argue that Maduro's alleged drug trafficking activities and the 2020 indictment against him provide legal grounds for the action.

Where Venezuela Stands Now: Leadership Vacuum and International Reaction

Following Maduro's capture, Venezuela's Supreme Court ordered Vice President Delcy Rodriguez to serve as acting president "to guarantee administrative continuity and the comprehensive defence of the Nation." Rodriguez appeared on state television to demand Maduro's immediate release, declaring, "There is only one president in Venezuela, and his name is Nicolás Maduro Moros." She called the operation a "kidnapping" and vowed to continue governing.

The international reaction has been sharply divided. Argentina's President Javier Milei praised Venezuela's new "freedom," while Mexico condemned the intervention and Brazil's President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva called it "unacceptable." Russia and China, both major backers of Venezuela, criticized the US action, with China's foreign ministry stating it "firmly opposes such hegemonic behaviour by the U.S., which seriously violates international law." Within Venezuela itself, reactions have been mixed—while pro-Maduro protesters took to the streets in Caracas, other Venezuelans expressed relief at his removal after years of economic crisis and political repression.

Casualty figures from the operation remain unclear. The Venezuelan government reports that "several deafening explosions rang out across Caracas" during the 30-minute operation, with strikes hitting Caracas as well as the states of Miranda, Aragua and La Guaira. An official speaking anonymously to The New York Times estimated at least 40 people were killed in the attacks, though Trump stated that no US forces were killed and only some were injured.

What Comes Next: The Future of US-Venezuela Relations and the Monroe Doctrine

The immediate future of Venezuela remains uncertain. Trump has stated that the US is "not afraid of boots on the ground if we have to" but has provided few details about how American control would actually work given that Maduro's government continues to function. The administration plans to bring in major US oil companies to refurbish Venezuela's degraded oil infrastructure, though experts warn this process could take years.

Longer term, the Venezuela operation raises profound questions about the future of the Monroe Doctrine itself. Some analysts see this as a revival of "gunboat diplomacy" reminiscent of the Roosevelt era, while others view it as an unprecedented expansion of the doctrine's scope. The operation also represents a significant test for international law and the norms governing intervention in sovereign states.

As Maduro faces trial in New York—scheduled to begin with an initial court appearance on Monday—and Venezuela navigates its political transition, the world will be watching to see how this chapter in the long history of the Monroe Doctrine unfolds. What began as a warning to European powers in 1823 has evolved into a justification for direct military intervention in the 21st century, demonstrating how historical foreign policy principles can be reinterpreted and applied in dramatically new contexts.

Key Takeaways: Understanding the Monroe Doctrine's Legacy

Several important points emerge from examining the Monroe Doctrine's history and current application. First, the doctrine represents one of the oldest continuous principles in US foreign policy, surviving for over 200 years through multiple reinterpretations. Second, its meaning has evolved significantly—from a defensive warning to Europe in 1823 to an assertive claim of US hemispheric leadership under Roosevelt to today's justification for regime change. Third, the doctrine has consistently served to justify US intervention in Latin America, though the Venezuela operation represents its most dramatic application in decades. Finally, the doctrine's future remains uncertain, with the Venezuela operation likely to provoke renewed debate about US-Latin American relations and the limits of hemispheric influence.